The Mayan Numeral System

Learning Outcomes

- Become familiar with the history of positional number systems

- Identify bases that have been used in number systems historically

- Convert numbers between bases

- Use two different methods for converting numbers between bases

Background

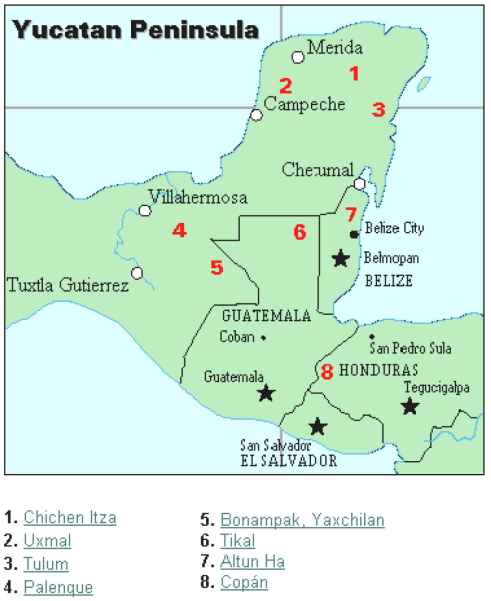

As you might imagine, the development of a base system is an important step in making the counting process more efficient. Our own base-ten system probably arose from the fact that we have 10 fingers (including thumbs) on two hands. This is a natural development. However, other civilizations have had a variety of bases other than ten. For example, the Natives of Queensland used a base-two system, counting as follows: “one, two, two and one, two two’s, much.” Some Modern South American Tribes have a base-five system counting in this way: “one, two, three, four, hand, hand and one, hand and two,” and so on. The Babylonians used a base-sixty (sexigesimal) system. In this chapter, we wrap up with a specific example of a civilization that actually used a base system other than 10. The Mayan civilization is generally dated from 1500 BCE to 1700 CE. The Yucatan Peninsula (see figure 16[footnote]http://www.gorp.com/gorp/location/latamer/map_maya.htm[/footnote]) in Mexico was the scene for the development of one of the most advanced civilizations of the ancient world. The Mayans had a sophisticated ritual system that was overseen by a priestly class. This class of priests developed a philosophy with time as divine and eternal.[footnote]Bidwell, James; Mayan Arithmetic in Mathematics Teacher, Issue 74 (Nov., 1967), p. 762–68.[/footnote] The calendar, and calculations related to it, were thus very important to the ritual life of the priestly class, and hence the Mayan people. In fact, much of what we know about this culture comes from their calendar records and astronomy data. Another important source of information on the Mayans is the writings of Father Diego de Landa, who went to Mexico as a missionary in 1549.

The Mayan civilization is generally dated from 1500 BCE to 1700 CE. The Yucatan Peninsula (see figure 16[footnote]http://www.gorp.com/gorp/location/latamer/map_maya.htm[/footnote]) in Mexico was the scene for the development of one of the most advanced civilizations of the ancient world. The Mayans had a sophisticated ritual system that was overseen by a priestly class. This class of priests developed a philosophy with time as divine and eternal.[footnote]Bidwell, James; Mayan Arithmetic in Mathematics Teacher, Issue 74 (Nov., 1967), p. 762–68.[/footnote] The calendar, and calculations related to it, were thus very important to the ritual life of the priestly class, and hence the Mayan people. In fact, much of what we know about this culture comes from their calendar records and astronomy data. Another important source of information on the Mayans is the writings of Father Diego de Landa, who went to Mexico as a missionary in 1549.

There were two numeral systems developed by the Mayans—one for the common people and one for the priests. Not only did these two systems use different symbols, they also used different base systems. For the priests, the number system was governed by ritual. The days of the year were thought to be gods, so the formal symbols for the days were decorated heads,[footnote]http://www.ukans.edu/~lctls/Mayan/numbers.html[/footnote] like the sample to the left[footnote]http://www.ukans.edu/~lctls/Mayan/numbers.html[/footnote] Since the basic calendar was based on 360 days, the priestly numeral system used a mixed base system employing multiples of 20 and 360. This makes for a confusing system, the details of which we will skip.

There were two numeral systems developed by the Mayans—one for the common people and one for the priests. Not only did these two systems use different symbols, they also used different base systems. For the priests, the number system was governed by ritual. The days of the year were thought to be gods, so the formal symbols for the days were decorated heads,[footnote]http://www.ukans.edu/~lctls/Mayan/numbers.html[/footnote] like the sample to the left[footnote]http://www.ukans.edu/~lctls/Mayan/numbers.html[/footnote] Since the basic calendar was based on 360 days, the priestly numeral system used a mixed base system employing multiples of 20 and 360. This makes for a confusing system, the details of which we will skip.

| Powers | Base-Ten Value | Place Name |

| 207 | 12,800,000,000 | Hablat |

| 206 | 64,000,000 | Alau |

| 205 | 3,200,000 | Kinchil |

| 204 | 160,000 | Cabal |

| 203 | 8,000 | Pic |

| 202 | 400 | Bak |

| 201 | 20 | Kal |

| 200 | 1 | Hun |

The Mayan Number System

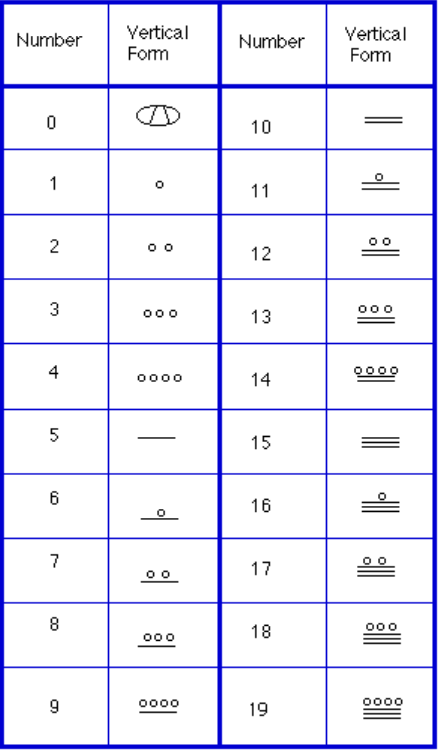

Instead, we will focus on the numeration system of the “common” people, which used a more consistent base system. As we stated earlier, the Mayans used a base-20 system, called the “vigesimal” system. Like our system, it is positional, meaning that the position of a numeric symbol indicates its place value. In the following table you can see the place value in its vertical format.[footnote]Bidwell[/footnote] In order to write numbers down, there were only three symbols needed in this system. A horizontal bar represented the quantity 5, a dot represented the quantity 1, and a special symbol (thought to be a shell) represented zero. The Mayan system may have been the first to make use of zero as a placeholder/number. The first 20 numbers are shown in the table to the right.[footnote]http://www.vpds.wsu.edu/fair_95/gym/UM001.html[/footnote]

Unlike our system, where the ones place starts on the right and then moves to the left, the Mayan systems places the ones on the bottom of a vertical orientation and moves up as the place value increases.

When numbers are written in vertical form, there should never be more than four dots in a single place. When writing Mayan numbers, every group of five dots becomes one bar. Also, there should never be more than three bars in a single place…four bars would be converted to one dot in the next place up. It’s the same as 10 getting converted to a 1 in the next place up when we carry during addition.

In order to write numbers down, there were only three symbols needed in this system. A horizontal bar represented the quantity 5, a dot represented the quantity 1, and a special symbol (thought to be a shell) represented zero. The Mayan system may have been the first to make use of zero as a placeholder/number. The first 20 numbers are shown in the table to the right.[footnote]http://www.vpds.wsu.edu/fair_95/gym/UM001.html[/footnote]

Unlike our system, where the ones place starts on the right and then moves to the left, the Mayan systems places the ones on the bottom of a vertical orientation and moves up as the place value increases.

When numbers are written in vertical form, there should never be more than four dots in a single place. When writing Mayan numbers, every group of five dots becomes one bar. Also, there should never be more than three bars in a single place…four bars would be converted to one dot in the next place up. It’s the same as 10 getting converted to a 1 in the next place up when we carry during addition.

Example

What is the value of this number, which is shown in vertical form?Answer:

Starting from the bottom, we have the ones place. There are two bars and three dots in this place. Since each bar is worth 5, we have 13 ones when we count the three dots in the ones place. Looking to the place value above it (the twenties places), we see there are three dots so we have three twenties.

Hence we can write this number in base-ten as:

(3 × 201) + (13 × 200) = (3 × 201) + (13 × 1) = 60 + 13 = 73

Hence we can write this number in base-ten as:

(3 × 201) + (13 × 200) = (3 × 201) + (13 × 1) = 60 + 13 = 73

Example

What is the value of the following Mayan number?

Answer: This number has 11 in the ones place, zero in the 20s place, and 18 in the 202 = 400s place. Hence, the value of this number in base-ten is: 18 × 400 + 0 × 20 + 11 × 1 = 7211.

Try It

Convert the Mayan number below to base 10.

Answer:

Answer: [latex]5617_{10} = 14,0,17_{20}[/latex]. Note that there is a zero in the 20’s place, so you’ll need to use the appropriate zero symbol in between the ones and 400’s places.

![]()

[footnote]http://forum.swarthmore.edu/k12/mayan.math/mayan2.html[/footnote]

[footnote]http://forum.swarthmore.edu/k12/mayan.math/mayan2.html[/footnote]

Next, put all of the symbols from both numbers into a single set of places (boxes), and to the right of this new number draw a set of empty boxes where you will place the final sum:

Next, put all of the symbols from both numbers into a single set of places (boxes), and to the right of this new number draw a set of empty boxes where you will place the final sum:

You are now ready to start carrying. Begin with the place that has the lowest value, just as you do with Arabic numbers. Start at the bottom place, where each dot is worth 1. There are six dots, but a maximum of four are allowed in any one place; once you get to five dots, you must convert to a bar. Since five dots make one bar, we draw a bar through five of the dots, leaving us with one dot which is under the four-dot limit. Put this dot into the bottom place of the empty set of boxes you just drew:

You are now ready to start carrying. Begin with the place that has the lowest value, just as you do with Arabic numbers. Start at the bottom place, where each dot is worth 1. There are six dots, but a maximum of four are allowed in any one place; once you get to five dots, you must convert to a bar. Since five dots make one bar, we draw a bar through five of the dots, leaving us with one dot which is under the four-dot limit. Put this dot into the bottom place of the empty set of boxes you just drew:

Now look at the bars in the bottom place. There are five, and the maximum number the place can hold is three. Four bars are equal to one dot in the next highest place.

Whenever we have four bars in a single place we will automatically convert that to a dot in the next place up. We draw a circle around four of the bars and an arrow up to the dots' section of the higher place. At the end of that arrow, draw a new dot. That dot represents 20 just the same as the other dots in that place. Not counting the circled bars in the bottom place, there is one bar left. One bar is under the three-bar limit; put it under the dot in the set of empty places to the right.

Now look at the bars in the bottom place. There are five, and the maximum number the place can hold is three. Four bars are equal to one dot in the next highest place.

Whenever we have four bars in a single place we will automatically convert that to a dot in the next place up. We draw a circle around four of the bars and an arrow up to the dots' section of the higher place. At the end of that arrow, draw a new dot. That dot represents 20 just the same as the other dots in that place. Not counting the circled bars in the bottom place, there is one bar left. One bar is under the three-bar limit; put it under the dot in the set of empty places to the right.

Now there are only three dots in the next highest place, so draw them in the corresponding empty box.

Now there are only three dots in the next highest place, so draw them in the corresponding empty box.

We can see here that we have 3 twenties (60), and 6 ones, for a total of 66. We check and note that 37 + 29 = 66, so we have done this addition correctly. Is it easier to just do it in base-ten? Probably, but that’s only because it’s more familiar to you. Your task here is to try to learn a new base system and how addition can be done in slightly different ways than what you have seen in the past. Note, however, that the concept of carrying is still used, just as it is in our own addition algorithm.

We can see here that we have 3 twenties (60), and 6 ones, for a total of 66. We check and note that 37 + 29 = 66, so we have done this addition correctly. Is it easier to just do it in base-ten? Probably, but that’s only because it’s more familiar to you. Your task here is to try to learn a new base system and how addition can be done in slightly different ways than what you have seen in the past. Note, however, that the concept of carrying is still used, just as it is in our own addition algorithm.